Unit Pricing: The Pricing Focus Leaders Use After Shrinkflation Hits Its Limit

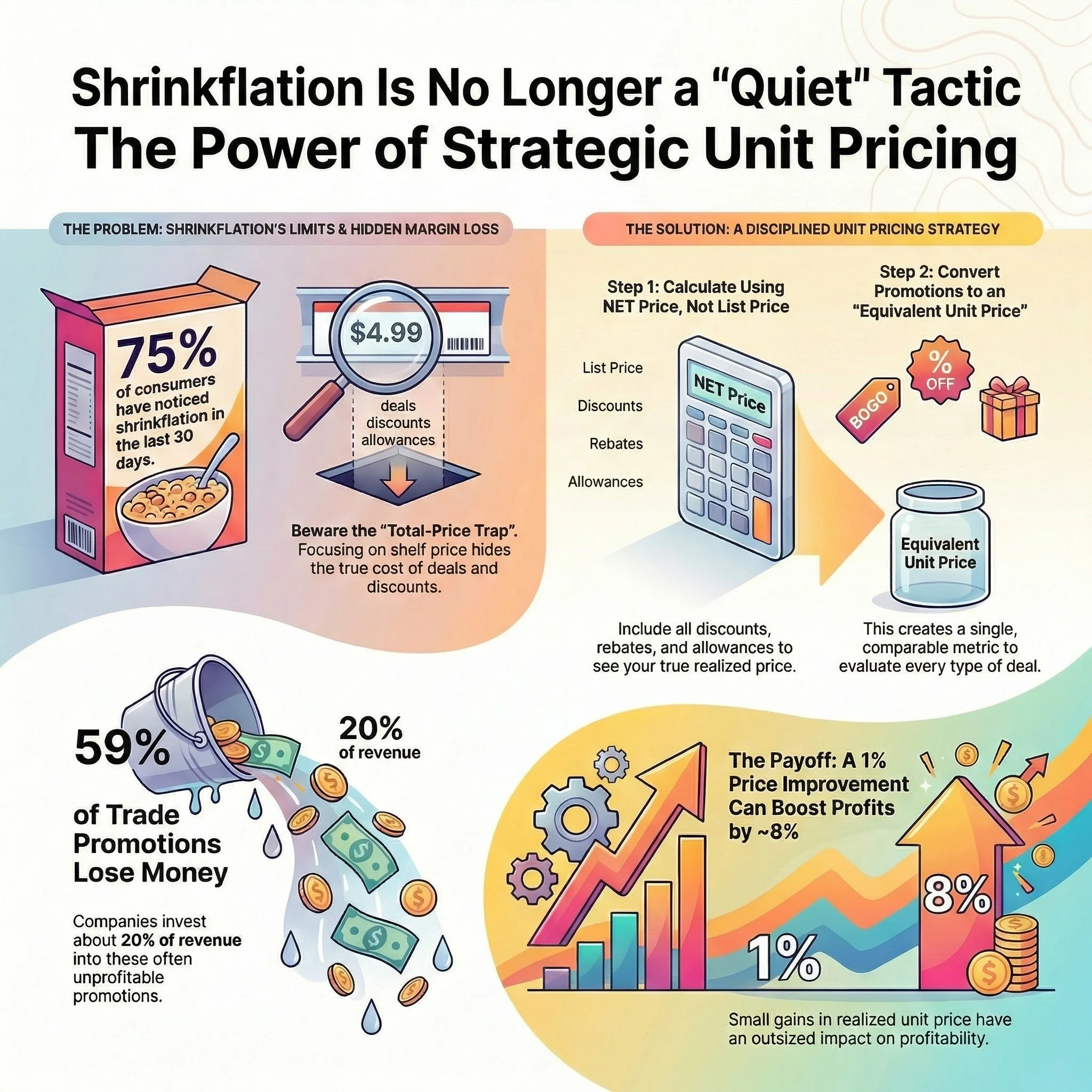

Shrinkflation reduced pack sizes, keeping shelf prices steady. However, consumers, retailers, and regulators are now closely watching this practice, and some markets are demanding more transparency. (Purdue Ag College)

The next pricing phase focuses less on hiding price increases and more on managing price per unit across packs, promotions, and channels to protect margins. This demands treating unit pricing as a core practice, not an afterthought.

This guide begins by outlining the core business challenge, clarifying key calculations, and illustrating how leaders use unit pricing to build more consistent pack-price architecture, optimize promotions, and maintain margin discipline. Key takeaway: mastering unit pricing drives better profitability and transparency across functions.

Unit pricing is the product or service price per standardized measure—dollars per ounce, pound, item, or case—calculated by dividing net price by the base quantity. This enables straightforward comparisons across pack sizes, SKUs, channels, and promotions.

Best Practices for Managing Unit Price

Select a single base unit per category and document it. Consistency prevents teams from debating calculations and allows them to focus on price architecture.

Base decisions on net price, not list price. Discounts, rebates, and allowances are part of real transactions and are recognized by accounting standards.

Shrinkflation is reaching its limits, as many markets require retail notices for size changes, and consumers can easily spot them. (Service Public)

Standardize pack sizes, units, and conversion factors so each SKU is comparable on a $/base-unit basis for portfolio analysis.

Leverage standardized unit pricing to construct pack-price ladders and identify margin leakage across channels, customers, and promotions.

Establish exception rules for bundles, variable-weight items, and promotions to keep unit pricing consistent as complexity grows.

What unit pricing is (and what it isn’t)

Many teams view unit pricing as just a tool for customer price display and quick spreadsheets. In reality, effective enterprise unit pricing is a cross-functional language linking marketing, sales, finance, and operations.

Unit price vs. total price

Total price is what the shopper sees (or what the customer is quoted) for the pack, case, or service line.

Unit price converts the offer to a consistent basis, such as $/oz, $/lb, $/each, or $/case.

Retail regulators treat this as a consumer transparency issue. In the EU, rules require retailers to show both the selling price and the unit price for products, because unit pricing helps buyers compare offers that don’t come in identical sizes. (European Commission)

In the US, NIST’s model regulations for unit pricing describe how unit prices should be expressed in standardized units (per 1 kilogram, 1 liter, 1 pound, etc.) so comparisons are straightforward. (NIST)

For pricing leaders, unit pricing enables comparison of offers not designed for easy evaluation. This gray area often harbors discounts and concessions, which can help or hurt profits.

Unit price vs. list price vs. net price

This distinction is more significant than it may initially appear.

List price is the published price (or the starting point).

Net price is what you actually collect after discounts, rebates, trade allowances, off-invoice deals, bill-backs, and terms.

Accounting guidance on revenue recognition treats transaction consideration as variable if it includes discounts, rebates, refunds, credits, incentives, or similar adjustments.

Shrinkflation was effective because it increased the unit price without altering the sticker price, allowing brands to raise the price per volume discreetly.

Two things are changing:

Consumers are paying more attention. A Purdue consumer sentiment report found that more than three-quarters of respondents noticed shrinkflation in the prior 30 days (survey sample size 1,452). (Purdue Ag College)

Regulators are reacting in some markets. France implemented a requirement for certain retailers to display a notice when a product’s quantity drops while its price remains the same or increases (the notice requirement began on July 1, 2024). (Service Public)

And in the US, the Government Accountability Office analyzed shrinkflation as one factor in consumer goods inflation, noting it contributed less than one-tenth of a percentage point to the overall increase they measured over their study period (which still matters politically, even if it’s a smaller slice of measured inflation). (fda.gov)

In summary, with shrinkflation now visible, pricing teams are moving toward transparent approaches with consistent pack architecture and unit pricing.

The unit pricing formula (with quick examples)

At the core, unit pricing is simple:

Unit price = Net price ÷ Quantity (in base units)

The complexity is in the details—terms like net price, quantity, and base units require careful consideration.

Example 1: Standard retail unit pricing per ounce

SKU A: $6.50 for 24 oz

Unit price = 6.50 ÷ 24 = $0.2708/oz

SKU B: $4.00 for 16 oz

Unit price = 4.00 ÷ 16 = $0.2500/oz

Though SKU A has a higher total price, it also has a higher price per ounce. This affects both consumer comparisons and pack-price ladder development.

Example 2: Shrinkflation shows up as a unit price increase

Now shrink SKU A from 24 oz to 22 oz, keep price at $6.50:

Unit price = 6.50 ÷ 22 = $0.2955/oz

This leads to a 9.1% increase in price per ounce, despite no sticker price change.

This is where unit pricing shifts from "retail math" to a strategic tool. Without clear visibility, pack architecture decisions are made in a fog.

Example 3: Promotions require an “equivalent unit price”

Promotions complicate comparisons. Consistent evaluation requires all offers to be converted to an equivalent unit price. The same 22 oz SKU at $6.50 with “BOGO 50%”:

Buy two units:

Price paid = 6.50 + (6.50 × 0.5) = 6.50 + 3.25 = $9.75

Total quantity = 22 oz + 22 oz = 44 oz

Equivalent unit price = 9.75 ÷ 44 = $0.2216/oz

Compare that to the base unit price ($0.2955/oz):

0.2216 ÷ 0.2955 ≈ 0.75 → an effective unit price reduction of about 25%.

For margin analysis, if gross margin is 40% at the base price, a 25% unit price reduction lowers the gross margin rate to 20%, assuming unit costs remain constant. This demonstrates how seemingly moderate promotions can significantly impact profitability when evaluated through unit economics.

From a consumer-protection standpoint, the FTC’s Guides Against Deceptive Pricing include guidance on “free” and bargain offers, emphasizing that the terms of the offer should be clear and that “free” isn’t a magic word that removes conditions.

To drive profitability, pricing teams must maintain a clear unit-price perspective in promotions, ensuring decisions center on value rather than just discount percentages. This is known as the Total-Price Trap.

If a promotion has been approved solely because the shelf price appears competitive, your team has encountered the Total-Price Trap.

The Total-Price Trap shows up in a few familiar places:

A multipack “value” offer that is actually higher $/oz than the single-serve.

A trade deal that looks fine as “15% off list,” but drops the net unit price below your margin floor once you include bill-backs and terms.

A bundle that wins a customer meeting, then loses money because the bundle mixes very different cost-to-serve profiles.

Executive focus on a single, robust unit-pricing metric empowers fact-based negotiations and confident, strategic decision-making.

Unit Pricing Strategy vs. Shrinkflation: The Net Price Formula

Why shrinkflation is hitting practical limits (and what replaces it)

Shrinkflation faces limitations that cannot be resolved through analysis alone:

Visibility is rising. Consumers and regulators are increasingly noticing and responding to size reductions. (Purdue Ag College)

Packaging and operations have hard limits. You can’t shrink forever without changing the product experience, packaging lines, or case configuration.

Retailers and consumers demand logical pack pricing. When pack-price ladders lack logic, category managers need to map competitors with a clearer value proposition in mind. McKinsey found consumer goods firms spend 20% of revenue on trade promotions, yet 59% (72% in the US) lost money in their cited data set. (natpromo.com)

Shrinkflation is typically replaced by a more disciplined combination of strategies:

Pack-price architecture that makes sense in unit terms

Promotions that are evaluated in equivalent unit price

Discount governance that keeps the net unit price inside guardrails

Unit pricing examples across retail, manufacturing, and B2B

The following three scenarios use illustrative figures to demonstrate the calculations and resulting business decisions.

Scenario A: CPG manufacturing (pack-price ladder breaks once discounts enter)

A snack manufacturer sells:

12-pack at $18 list (=$1.50/unit)

24-pack at $32 list (=$1.33/unit). At first glance, the pack-price ladder appears logical: larger packs offer a lower unit price.

Now add the real world:

12-pack: average discounts and allowances = 10%

Net unit price = (18 × 0.90) ÷ 12 = $16.20 ÷ 12 = $1.35/unit

24-pack: average discounts and allowances = 2Net unit price = (32 × 0.78) ÷ 24 = $24.96 ÷ 24 = $1.04 per unit

If the cost is $0.90/unit, the difference in gross profit per unit is stark:

12-pack gross profit ≈ 1.35 − 0.90 = $0.45/unit

24-pack gross profit ≈ 1.04 − 0.90 = $0.14/unit

This illustrates the limitations of list-based architecture. While the ladder is constructed using list prices, profitability is determined by net unit price.

A Bain analysis often cited in pricing work found that a 1% improvement in realized price can increase operating profits by roughly 8% (all else equal). That’s why small improvements in realized unit price matter so much. (Bain)

Scenario B: B2B distribution (case vs each, plus terms)

An industrial distributor sells fasteners:

Case of 100: $120, customer picks up from the warehouse.

Unit price = $1.20/each

Case of 250: $280, delivered to customer.

Ticket unit price = $1.12/each

Initially, the 250-pack appears to offer better value.

Now include terms:

Delivery cost allocated: $15 per case

Adjusted net = 280 − 15 = 265

Unit net price = 265 ÷ 250 = $1.06/each

Annual rebate: 2% on total purchases

Unit net price = 1.06 × 0.98 = $1.04/each

That is still cheaper. However, the larger concern is governance. Most B2B teams lack a standardized, repeatable method to translate rebates, freight, and discounts into a net unit price. This often leads to recurring disputes between sales and finance, and the exception list grows.

Scenario C: Retail (promotions look different once converted to unit price)

A beverage brand has:

Single 16 oz at $2.49 → $0.1556/oz

6-pack of 12 oz (72 oz) at $8.49 → $0.1179/oz

Promo: 20% off the 6-pack → $6.79 → $0.0943/oz

Evaluating promotions solely by percentage discount may result in approving a 20% reduction without recognizing its broader category impact: it makes the multipack about 39% cheaper per ounce than the single (0.0943 vs 0.1556).

This can shift volume away from higher-margin single-serve channels and encourage consumers to delay purchases until promotions are available.

Unit pricing does not dictate whether to run a promotion; rather, it clarifies the true impact in unit terms, enabling informed decision-making.

Why unit pricing matters for pricing and revenue management

Unit pricing becomes strategic when it’s used in three places: architecture, promotions, and governance.

1) Price architecture and pack-price ladders

A coherent good/better/best ladder requires that all packs align. Unit pricing quickly reveals common architecture issues, such as:unit pricing exposes quickly:

“Value packs.” The mid-tier pack is priced lower per unit than the value pack, resulting in a ladder inversion.

New product introductions that unintentionally undercut the core range when normalized

2) Promotion economics and trade spend discipline

Trade spend is too significant to manage informally. McKinsey’s research shows that approximately 20% of revenue is invested in trade promotions, with a majority resulting in losses. This highlights a substantial opportunity for improvement. Unit pricing provides clarity on questions that teams often find challenging to address:

Which promo mechanics lower the unit price the most?

What unit price floors are required to keep the margin intact by channel?

Are we generating incremental volume, or merely shifting buyers across pack sizes and purchase timing?

McKinsey also notes that top performers in trade promotion returns can outperform peers by multiples (their research cites about 5 times more returns for leaders). (natpromo.com)

3) Discount governance and price realization

All businesses offer discounts. The distinction between disciplined and uncontrolled discounting lies in the ability to identify when the net unit price falls outside established guardrails and to address it promptly.

That means:

Defining unit price floors by category, customer segment, and channel

Tracking exceptions and their P&L impact, training commercial teams with specific deal examples rather than abstract policy presentations)

Revology’s work in pricing and revenue growth management centers on building this kind of visibility and discipline across pricing, discounts, and promotions.

Unit pricing in construction has the same lesson (and a useful parallel).

The Federal Acquisition Regulation (FAR) describes unit-price contracting in construction contexts where work is priced per unit and quantities are measured for payment.

It goes further: FAR includes a clause on the Integrity of Unit Prices, aimed at preventing overstated unit prices in one line item that are “balanced” by understated prices elsewhere (a classic way to shift risk and cash flow).

This governance principle is equally relevant for CPG and B2B pricing teams:

Don’t let unit prices get distorted inside a deal, bundle, or promo “basket.”

Make unit economics comparable, measurable, and reviewable.

How to implement unit pricing as a discipline

If unit pricing remains confined to ad hoc spreadsheets, it will not influence decision-making. The following is a practical implementation sequence suitable for most CPG and B2B environments.

Step 1: Define base units and conversion rules (before you touch dashboards)

Pick the base unit by category (examples):

Snacks: $/oz

Frozen: $/lb

Beverages: $/fl oz

Industrial parts: $/each

Chemicals: $/gallon or $/kg

Then define conversions:

oz ↔ lb

case ↔ each

multipack ↔ single

variable-weight items (where quantity is measured at sale)

NIST’s model guidance underscores that unit pricing should be expressed in standardized base units, which is exactly what you’re doing internally for business decision-making. (NIST)

Step 2: Build “net price” the same way finance sees it

At minimum, capture:

Invoice price

Off-invoice discounts

Bill-backs

Rebates and accruals

Trade allowances

This is a practical requirement. Revenue recognition standards treat discounts, rebates, and similar items as components of variable consideration.

Step 3: Normalize pack sizes and promotional mechanics

This is where unit pricing becomes usable:

Map each SKU to base units.

Create “equivalent unit price” rules for:

BOGO variants

multipacks

percent-off offer. If the equivalent unit price cannot be calculated, promotional options cannot be compared accurately. Compare promo options cleanly.

Step 4: Set guardrails and exception rules

Guardrails should be actionable rather than theoretical:

Unit price floor by category and channel

Floor by customer segment for B2B

“Stoplight” thresholds (green, yellow, red)

Written exceptions: new product launch, end-of-life, clearance, strategic accounts

Step 5: Put the insights where decisions happen

If unit pricing is managed solely by finance, sales teams may disregard it. Conversely, if managed only by sales, finance may question its validity.

A practical approach is to publish a small set of standard views:

Current net unit price vs guardrail by customer and SKU

Promo equivalent unit price vs baseline

Pack ladder view (unit price across pack sizes)

Margin per base unit trend

Revology often supports this through pricing and revenue growth management advisory work and commercial analytics transformation, aligning data, metrics, and decision routines across teams.

Before vs After: What changes when unit pricing is governed

VisibilityUnit prices exist on shelf tags or in scattered spreadsheets; net unit price is hard to see consistently.Standard unit price and net unit price are defined by category; pack and promo conversions are documented and repeatable.SpeedEvery trade review becomes a custom analysis; debates center on list price and percent-off.Standard views answer the same questions every week: unit price, equivalent unit price, and margin impact.ConsistencyDifferent teams use different units, different “net” definitions, and different promo math.One definition set for base units, net price, and promo conversions; exceptions are written down and reviewed.Profit ImpactPromotions and discounts can cut unit price more than expected; margin erosion shows up late.Guardrails flag deals and promos that fall below floors early enough to change course.Sales EnablementSales hears “no” without clear deal math; exceptions pile up near quarter-end.Sales gets clear unit price bands and example deals; exceptions are tied to measurable tradeoffs.Governance/ControlsNo consistent floor logic; post-event analysis is uneven; accountability is fuzzy.Floors, thresholds, and exception workflows are explicit; post-event reviews follow a standard routine.

Common objections (and practical answers)

“We already have the unit price on the shelf tag.”

Shelf unit price is a starting point, but it seldom accounts for trade spend, bill-backs, rebates, or B2B terms. Since your P&L is based on net price, your unit pricing strategy should be as well.

“Our data isn’t clean enough.”

Most organizations begin with inconsistent units of measure and irregular promotional codes. The solution is to define the initial scope as follows:

Start with the top categories that represent most revenue.

Normalize a small set of pack types and promo mechanics.

Improve the conversion table over time as issues are found.

“Sales will fight unit-price floors.”

Resistance typically arises from unexpected changes rather than from structured processes. A unit price floor explained in margin terms, with clearly defined exceptions, is more acceptable than frequent renegotiations.

“This sounds like a big system project.”

It actually does not require a large-scale system project. Early progress can be achieved through standard definitions, conversion tables, and a few repeatable reports. System implementation can follow as needed.

Here’s an illustrative scenario that shows why unit pricing is so tied to EBITDA thinking.

Assume:

Current list price: $10.00/unit

Average discounts and allowances: 20%

Net price: $8.00/unit

Unit cost: $5.20

Volume: 100,000 units

Baseline:

Revenue = 8.00 × 100,000 = $800,000

Gross profit per unit = 8.00 − 5.20 = $2.80

Total gross profit = 2.80 × 100,000 = $280,000

Now raise the list price by 2% to $10.20 and hold discounts at 20%:

Net price = 10.20 × 0.80 = $8.16

If elasticity is −1.2, a 2% price increase implies volume drops about 2.4%

New volume = 100,000 × 0.976 = 97,600

New results:

Revenue = 8.16 × 97,600 = $796,416

Gross profit per unit = 8.16 − 5.20 = $2.96

Total gross profit = 2.96 × 97,600 = $288,896

While revenue decreases slightly, gross profit increases by $8,896. Pricing is so sensitive. Bain’s pricing research highlights that even a 1% improvement in realized price can have an outsized effect on operating profits. (Bain)

Unit pricing helps you run this analysis consistently across packs and promos, not just a single SKU.

KPIs that make unit pricing useful (not academic)

A few metrics show up again and again in high-functioning pricing teams:

Net unit price by SKU, customer, and channel (core metric)

Unit price variance vs target (how far from your intended architecture)

Promo equivalent unit price vs baseline (how aggressive was the deal, really)

Mix-adjusted net unit price (separates mix shifts from true price changes)

Gross profit per base unit (margin in the same unit pricing language)

Exception rate (share of revenue below floor, with reason codes)

Post-promo payback (did the volume and mix after the promo justify the unit price cut)

Given that trade promotions account for approximately 20% of revenue and are often unprofitable, these KPIs are essential controls rather than optional metrics. (natpromo.com)

Common pitfalls to watch for

Using the list price in unit pricing dashboards. It makes the picture look cleaner than it is. Net price is harder but real.

Mixing base units inside a category. That creates false comparisons and poor architectural decisions. (NIST)

Ignoring promo mechanics in the math. Percent-off discounts are not equivalent across packs, and BOGO variants can dramatically change the equivalent unit price.

Treating bundles as one SKU without unpacking units. You’ll misread the economics and blame the wrong team when the P&L misses.

Forgetting the cost-to-serve story. Unit price is only half the equation.

FAQ

What is unit pricing in retail?

In retail, unit pricing is the price per standard unit of measure (e.g., $/oz or $/lb) to help shoppers compare products sold in different sizes. In many jurisdictions, rules require unit prices to be displayed in standardized units for transparency. (European Commission)

How do you calculate unit pricing?

Pick a base unit (for example, ounces), convert the package quantity into that base unit, then divide the net price by the quantity:

Unit price = Net price ÷ Quantity (base units)

For promotions, calculate the equivalent unit price by dividing the total price paid by the total units received.

Is unit pricing the same as unit cost?

No. Unit pricing is what you charge per unit. Unit cost is the cost per unit. Pricing decisions should consider both, especially when promotions and terms materially change the net unit price.

Why does unit pricing matter more after shrinkflation?

Shrinkflation changes the unit price without changing the sticker price, and consumers and regulators are increasingly sensitive to it. If shrinkflation becomes harder to use, companies need greater discipline in pack architecture and promotions, which requires consistent unit-price visibility. (Service Public)

How do I use unit pricing in B2B?

Use it to normalize different pack formats, terms, and incentives into a net unit price, then set guardrails by customer segment and channel. Without that, discount governance becomes a recurring argument instead of a controlled process.

The next step: a unit pricing diagnostic (what Revology does)

If your team is serious about unit pricing strategy, start with a short diagnostic:

Pull a representative slice of transactions (and promotions if applicable)

Rebuild net price using the same components finance uses

Normalize units of measure and pack conversions.

Identify where the unit price falls outside the intended pack ladders and margin floors.

Put guardrails in place, with written exceptions tied to measurable tradeoffs.

Revology’s Pricing & Revenue Growth Management advisory work and Commercial Analytics Transformation services are built around this kind of practical, cross-functional pricing discipline (pricing, discounting, promotions, and margin analytics tied together).

If you want, book a pricing and revenue management diagnostic call with Revology and bring two things: your top categories and your last promotion calendar. You’ll get a clear view of where net unit price is helping you and where it’s quietly costing you margin.

LinkedIn expert

Shrinkflation bought time. It’s getting harder to use as a quiet margin fix.

A Purdue consumer sentiment report found that more than three-quarters of respondents noticed shrinkflation in the prior 30 days. And in France, retailers have had to display notices when quantity drops while price stays flat or rises (effective July 1, 2024). (Purdue Ag College)

So what replaces shrinkflation?

For most CPG teams, it’s not one tactic. It’s disciplined unit pricing: converting every pack and promo to comparable $/oz, $/lb, or $/each using net price (after discounts, rebates, and allowances).

Why it matters: Trade promotions are massive. McKinsey reports that consumer goods companies invest about 20% of revenue in trade promotions, and a majority of promotions can lose money in many environments. (natpromo.com)

If your trade reviews still center on “% off list” instead of equivalent unit price, you’re guessing at profitability.

I wrote a practical guide on unit pricing strategy, formulas, and examples (retail + B2B), plus what to implement first so the math actually changes decisions.

Subscribe to

Revology Analytics Insider

Revenue Growth Analytics thought leadership by Revology?

Use the form below to subscribe to our newsletter.